Researchers paired proteins with a process that amplifies RNA which could be used to detect cancer cell

HIV has no cure. It’s not quite the implacable scourge it was throughout the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to education, prophylactics, and drugs like PrEP. But still, no cure.

Genetically-modified humans: what is CRISPR and how does it work?

Last week, a group of biologists published research detailing how they hid an anti-HIV CRISPR system inside another type of virus capable of sneaking past a host’s immune system. What’s more, the virus replicated and snipped HIV from infected cells along the way. At this stage, it works in mice and rats, not people. But as a proof of concept, it means similar systems could be developed to fight a huge range of diseases—herpes, cystic fibrosis, and all sorts of cancers.

Those diseases are all treatable, to varying degrees. But the problem with treatments is you have to keep doing them in order for them to work. “The current anti-retroviral therapy for HIV is very successful in suppressing replication of the virus,” says Kamel Khalili, a neurovirologist at Temple University in Philadelphia and lead author of the recent research, published in Molecular Therapy. “But that does not eliminate the copies of the virus that have been integrated into the gene, so any time the patient doesn’t take their medication the virus can rebound.” Plus treatments can — and often do — fail.

Gene therapy has promised to revolutionise medicine since the 1970s, when a pair of researchers introduced the concept of using viruses to replace bad DNA with good DNA. The first working model was tested on mice in the 1980s, and by the 1990s researchers were using gene therapies — with limited success — to treat immune and nutrition deficiencies. Then, in 1999, a patient in a University of Pennsylvania gene therapy trial named Jesse Gelsinger died from complications. The tragedy temporarily skid-stopped the whole field. Gene therapy had been steadily getting its groove back, but the 2012 discovery that CRISPR could make easy, and accurate, cuts on human genes, added more vigor.

CRISPR as an agent for curing HIV has its own problems. For one, it has to be able to snip away the HIV from an infected cell without damaging any of the surrounding DNA. HIV mutates and evolves, so Khalili and his co-authors couldn’t just program their CRISPR system with a single genetic mugshot. Instead, they had to target enough unchanging sections that were also critical to the virus’ survival.

Their next challenge was delivering the system to a critical mass of infected cells. First, you have to get it past the immune system – which is programmed to attack any non-foreign object entering the body. They did this by packing their CRISPR system inside another type of virus called AAV (short for adeno associated virus). “AAVs are a very small helper virus, they can’t actually replicate in a cell on their own unless they have another virus there to help it along,” says Keith Jerome, a microbiologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre in Seattle. “The great thing about AAVs is they cause essentially no immune system response in humans.” Although that’s not always true. Jesse Gelsinger died in 1999 because his immune system overreacted to the AAVs he’d been given in his gene therapy trial. So doctors hoping to prescribe AAV-based gene therapy have to be aware of patients’ prior exposure.

In order to get approved for human use, this type of CRISPR-borne cure would have to be both safe and effective. This study got part of the way but was going strictly for efficacy: Does this work? Khalili and his co-authors treated mice and rat model with strains of HIV that were latent; hiding away in cellular DNA—and others where the HIV was actively replicating. Then they used it on mice grafted with human cells. In all three cases, HIV rates went down significantly.

Other good news on the safety front: there’s no evidence their trial made any off-target cuts.

Khalili believes he can get close enough. According to him, the CRISPR system doesn’t need to eliminate all the HIV-infected cells, just enough so an HIV-patient’s immune system can get strong enough to take care of the rest on its own. “I strongly believe in the gene-editing strategy, and with my 30 years in HIV research, I think this is the one that is going to take us to the end.”

He’s not the only optimist. “The advantage of using a virus as your delivery system is it can infect virtually every cell,” says Jianhua Luo, a pathologist at the University of Pittsburgh. Luo is using a similar CRISPR-in-a-virus system to target cancerous DNA in cells.

And curing HIV could be a proof-of-concept for other diseases – even genetic diseases people are born with. Although the virus starts as a simple infection, once it becomes part of a person’s chromosome, it essentially becomes a genetic disease.

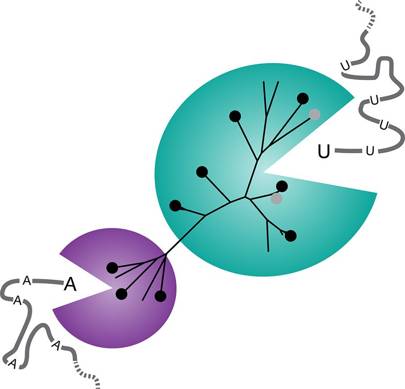

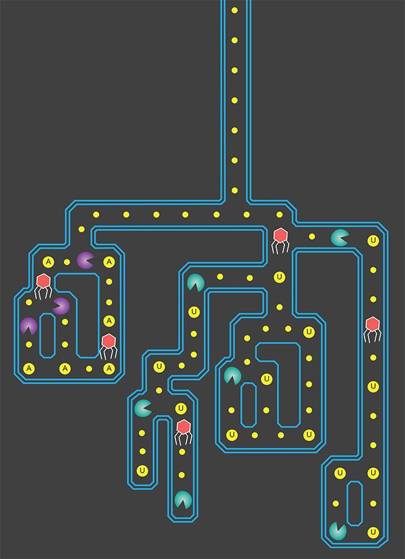

How CRISPR-Cas13a enzymes behave like Pac-man

- The CRISPR-Cas13a family, formerly referred to as CRISPR-C2c2, is related to CRISPR-Cas9, which is leading biomedical research and treatment into gene editing.

- However, while the Cas9 protein cuts double-stranded DNA at specific sequences, the Cas13a protein – a nucleic acid-cutting enzyme referred to as a nuclease – latches onto specific RNA sequences. This means it not only cuts that specific RNA, but runs amok to cut and destroy all RNA present.

- “Think of binding between Cas13a and its RNA target as an on-off switch — target binding turns on the enzyme to go be a Pac-Man in the cell, chewing up all RNA nearby,” researcher Alexandra East-Seletsky said. This RNA killing spree can kill the cell.

- Three of the new Cas13a variants also cut RNA at adenine. This difference allows simultaneous detection of two different RNA molecules, such as from two different viruses.

These new enzymes are variants of a CRISPR protein, Cas13a, which the UC Berkeley researchers reported last September in Nature, and could be used to detect specific sequences of RNA, such as from a virus. The team showed that once CRISPR-Cas13a binds to its target RNA, it begins to indiscriminately cut up all RNA making it "glow" to allow signal detection.

Expand your mind with WIRED's picks of the best podcasts

Two teams of researchers at the Broad Institute subsequently paired CRISPR-Cas13a with the process of RNA amplification to showed that the system, dubbed Sherlock, could detect viral RNA at extremely low concentrations, such as the presence of dengue and Zika viral RNA, for example. Such a system could be used to detect any type of RNA, including RNA distinctive of cancer cells.

Imagine a world where, instead of removing her breasts, Angelina Jolie could instead have taken a dose of genes that snip away the BRCA2 genes that threatened her with cancer. That’s the difference between a treatment and a cure.

Nick Stockton is a staff writer for WIRED US. This article originally appeared on WIRED. It has been updated to reference the new University of California, Berkeley research.

No comments:

Post a Comment